Federal Reserve System

| Federal Reserve System | |||||

|

|||||

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman | Ben Bernanke | ||||

| Central bank of | United States | ||||

| Currency | U.S. dollar | ||||

| ISO 4217 Code | USD | ||||

| Base borrowing rate | 0%-0.25%[3] | ||||

| Base deposit rate | 3.5% | ||||

| Website | federalreserve.gov | ||||

| Public finance |

|---|

|

| Sources of government revenue |

| Tax and non-tax revenue |

| Government policy |

| Fiscal · Monetary · Trade · Policy mix |

| Fiscal policy |

| Tax policy (see taxation series) Government revenue · Government debt Government spending (Deficit spending) Budget deficit and surplus |

| Monetary policy |

| Money supply · Central bank Gold standard · Fiat currency |

| Trade policy |

| Balance of trade · Tariff · Tariff war Free trade · Trade pact |

| See also |

| Taxation series · Project |

| Banking in the United States | |

|

Monetary policy |

|

|

Regulation |

|

|

Lending |

|

|

Deposit accounts |

|

|

Deposit account insurance |

|

|

Electronic funds transfer (EFT) |

|

|

Check Clearing System |

|

|

Types of bank charter |

|

The Federal Reserve System (also known as the Federal Reserve, and informally as the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created in 1913 with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, and was largely a response to a series of financial panics, particularly a severe panic in 1907.[1][2][3] Over time, the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System have expanded and its structure has evolved.[2][4] Events such as the Great Depression were major factors leading to changes in the system.[5] Its duties today, according to official Federal Reserve documentation, are to conduct the nation's monetary policy, supervise and regulate banking institutions, maintain the stability of the financial system and provide financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions.[6]

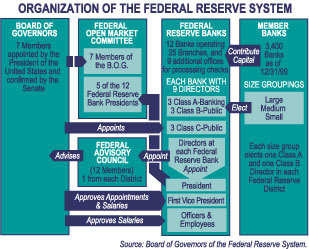

The Federal Reserve System's structure is composed of the presidentially appointed Board of Governors (or Federal Reserve Board), the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks located in major cities throughout the nation, numerous other private U.S. member banks and various advisory councils.[7][8][9] This division of responsibilities of the central bank falls into several separate and independent parts, some private and some public. The result is a structure that is considered unique among central banks. It is also unusual in that an entity (the U.S. Department of the Treasury) outside of the central bank creates the currency used.[10]

According to its board of governors, the Federal Reserve is independent from government as "its decisions do not have to be ratified by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branch of government." However, it derives its authority from the US Congress and is subject to congressional oversight. Additionally, the board members, chairman, and vice-chairman and their salaries are chosen by the President. Thus the Federal Reserve has both private and public aspects.[11] The U.S. Government receives all of the system's annual profits after a statutory dividend of 6% on member banks' capital investment is paid, and an account surplus is maintained. The Federal Reserve transferred a record amount of $45 billion to the U.S. Treasury in 2009.[12]

History

Central banking in the United States

The first paper money issued in the United States was by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1690. Soon other colonies began printing their own money as well. The demand for currency in the colonies was due to the scarcity of coins, which had been the primary means of trade at the time.[13] A colony's currency was used to pay for its expenses, as well as a means to loan money to the colony's citizens. The bills quickly became the primary means of exchange within the colonies, and were even used in financial transactions with other colonies.[14] However, some currencies were not redeemable in gold and silver, which caused their value to depreciate quickly.[13]

The first attempt at a national currency was during the Revolutionary war. In 1775 the Continental Congress issued paper currency, and called their bills "Continentals". But the money was not backed by gold or silver and its value depreciated quickly.[13]

In 1791, which was after the U.S. Constitution was ratified, the government granted the First Bank of the United States a charter to operate as the U.S.'s central bank until 1811.[13] Unlike the prior attempt at a centralized currency, the increase in the federal government's power—granted to it by the constitution—allowed national central banks to possess a monopoly on the minting of U.S currency.[15] Nonetheless, The First Bank of the United States came to an end when President Madison refused to renew its charter. The Second Bank of the United States met a similar fate under President Jackson. Both banks were based upon the Bank of England.[16] Ultimately, a third national bank—known as the Federal Reserve—was established in 1913 and still exists to this day. The time line of central banking in the United States is as follows:[17][18][19]

- 1791–1811

- 1811–1816

- No central bank

- 1816–1836

- 1837–1862

- Free Bank Era

- 1846-1921

- Independent Treasury System

- 1863–1913

- National Banks

- 1913–Present

- Federal Reserve System

Creation of First and Second Central Bank

The first U.S. institution with central banking responsibilities was the First Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress and signed into law by President George Washington on February 25, 1791 at the urging of Alexander Hamilton. This was done despite strong opposition from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, among numerous others. The charter was for twenty years and expired in 1811 under President James Madison, because Congress refused to renew it.[20]

In 1816, however, Madison revived it in the form of the Second Bank of the United States. Early renewal of the bank's charter became the primary issue in the reelection of President Andrew Jackson. After Jackson, who was opposed to the central bank, was reelected, he pulled the government's funds out of the bank. Nicholas Biddle, President of the Second Bank of the United States, responded by contracting the money supply to pressure Jackson to renew the bank's charter forcing the country into a recession, which the bank blamed on Jackson's policies. Interestingly, Jackson is the only President to completely pay off the national debt. The bank's charter was not renewed in 1836. From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank. From 1862 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act. A series of bank panics, in 1873, 1893, and 1907, provided strong demand for the creation of a centralized banking system.

Creation of Third Central Bank

The main motivation for the third central banking system came from the Panic of 1907, which caused renewed demands for banking and currency reform.[21] During the last quarter of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century the United States economy went through a series of financial panics.[22] According to many economists, the previous national banking system had two main weaknesses: an inelastic currency and a lack of liquidity.[22] In 1908, Congress enacted the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, which provided for an emergency currency and established the National Monetary Commission to study banking and currency reform.[23] The National Monetary Commission returned with recommendations which later became the basis of the Federal Reserve Act, passed in 1913.

Federal Reserve Act

The head of the bipartisan National Monetary Commission was financial expert and Senate Republican leader Nelson Aldrich. Aldrich set up two commissions—one to study the American monetary system in depth and the other, headed by Aldrich himself, to study the European central banking systems and report on them.[23] Aldrich went to Europe opposed to centralized banking, but after viewing Germany's monetary system he came away believing that a centralized bank was better than the government-issued bond system that he had previously supported.

In early November 1910, Aldrich met with five well known members of the New York banking community to devise a central banking bill. Paul Warburg, an attendee of the meeting and long time advocate of central banking in the U.S., later wrote that Aldrich was "bewildered at all that he had absorbed abroad and he was faced with the difficult task of writing a highly technical bill while being harassed by the daily grind of his parliamentary duties."[24] After ten days of deliberation, the bill, which would later be referred to as the "Aldrich Plan", was agreed upon. It had several key components including: a central bank with a Washington based headquarters and fifteen branches located throughout the U.S. in geographically strategic locations, and a uniform elastic currency based on gold and commercial paper. Aldrich believed a central banking system with no political involvement was best, but was convinced by Warburg that a plan with no public control was not politically feasible.[24] The compromise involved representation of the public sector on the Board of Directors.[25]

Aldrich's bill was met with much opposition from politicians. Critics were suspicious of a central bank, and charged Aldrich of being biased due to his close ties to wealthy bankers such as J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Aldrich's son-in-law. Most Republicans favored the Aldrich Plan,[25] but it lacked enough support in Congress to pass because rural and western states viewed it as favoring the "eastern establishment".[1] In contrast, progressive Democrats favored a reserve system owned and operated by the government; they believed that public ownership of the central bank would end Wall Street's control of the American currency supply.[25] Conservative Democrats fought for a privately owned, yet decentralized, reserve system, which would still be free of Wall Street's control.[25]

The original Aldrich Plan was dealt a fatal blow in 1912, when Democrats won the White House and Congress.[24] Nonetheless, President Woodrow Wilson believed that the Aldrich plan would suffice with a few modifications. The plan became the basis for the Federal Reserve Act, which was proposed by Senator Robert Owen in May 1913. The primary difference between the two bills was the transfer of control of the Board of Directors (called the Federal Open Market Committee in the Federal Reserve Act) to the government.[1][20] The bill passed Congress in late 1913[26][27] on a mostly partisan basis, with most Democrats voting "yea" and most Republicans voting "nay".[20]

1944-1971: Bretton Woods Era

In July 1944, 730 delegates from all 44 Allied nations gathered at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, to build a new international monetary system, which was in serious threat due to damage incurred during the Great Depression and the mounting debt of the Second World War. Their main objective was the cultivation of trade, which relied on the easy convertibility of currencies. Negotiators at the Bretton Woods conference, fresh from what they perceived as a disastrous experience with floating rates in the 1930s, concluded that major monetary fluctuations could stall the free flow of trade. Planners fundamentally supported a capitalistic approach , but favored tight control on currency values.

The agreement established the rules for commercial and financial relations among the world's major industrial states. The Bretton Woods system was the first example of a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent nation-states. Its chief feature was to require that each country adopt a monetary policy that maintained its exchange rate with gold to within plus or minus one percent of a specified value. To do this, they set up a system of fixed exchange rates using the U.S. dollar (which was on the gold standard itself) as a reserve currency. The planners established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) to regulate the newly devised system.

In the face of increasing financial strain, however, the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, after U.S. President Richard Nixon unilaterally terminated convertibility of the dollars to gold. This action caused considerable financial stress in the world economy and created the unique situation whereby the United States dollar became the "reserve currency" in the states that had signed the agreement.

1971-Present: Dollar Reserve Standard

Under the dollar reserve standard, the U.S. dollar was the most favored currency for nations of the world to use as reserves, which continued as a trend for over 30 years.[28] At the beginning of the dollar reserve standard, the 1970s became a period of high inflation.[29] As a result, in July 1979 Paul Volcker was nominated by President Carter as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. He tightened the money supply, and by 1986 inflation had fallen sharply.[30] In October 1979 the Federal Reserve announced a policy of "targeting" money aggregates and bank reserves in its struggle with double-digit inflation.[31]

In January 1987, with retail inflation at only 1%, the Federal Reserve announced it was no longer going to use money-supply aggregates, such as M2, as guidelines for controlling inflation, even though this method had been in use from 1979, apparently with great success. Before 1980, interest rates were used as guidelines; inflation was severe. The Fed complained that the aggregates were confusing. Volcker was chairman until August 1987, whereupon Alan Greenspan assumed the mantle, seven months after monetary aggregate policy had changed.[32]

Key laws

Key laws affecting the Federal Reserve have been:[33]

- Federal Reserve Act

- Glass-Steagall Act

- Banking Act of 1935

- Employment Act of 1946

- Federal Reserve-Treasury Department Accord of 1951

- Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 and the amendments of 1970

- Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977

- International Banking Act of 1978

- Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (1978)

- Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980)

- Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (1999)

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (2008)

Purpose

The primary motivation for creating the Federal Reserve System was to address banking panics.[2] Other purposes are stated in the Federal Reserve Act, such as "to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes".[34] Before the founding of the Federal Reserve, the United States underwent several financial crises. A particularly severe crisis in 1907 led Congress to enact the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. Today the Fed has broader responsibilities than only ensuring the stability of the financial system.[35]

Current functions of the Federal Reserve System include:[6][35]

- To address the problem of banking panics

- To serve as the central bank for the United States

- To strike a balance between private interests of banks and the centralized responsibility of government

- To supervise and regulate banking institutions

- To protect the credit rights of consumers

- To manage the nation's money supply through monetary policy to achieve the sometimes-conflicting goals of

- To maintain the stability of the financial system and contain systemic risk in financial markets

- To provide financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions, including playing a major role in operating the nation's payments system

- To facilitate the exchange of payments among regions

- To respond to local liquidity needs

- To strengthen U.S. standing in the world economy

Addressing the problem of bank panics

Bank runs occur because banking institutions in the United States are only required to hold a fraction of their depositors' money in reserve. This practice is called fractional-reserve banking. As a result, most banks invest the majority of their depositors' money. On rare occasion, too many of the bank's customers will withdraw their savings and the bank will need help from another institution to continue operating. Bank runs can lead to a multitude of social and economic problems. The Federal Reserve was designed as an attempt to prevent or minimize the occurrence of bank runs, and possibly act as a lender of last resort if a bank run does occur. Many economists, following Milton Friedman, believe that the Federal Reserve inappropriately refused to lend money to small banks during the bank runs of 1929.[37]

Elastic currency

One way to prevent bank runs is to have a money supply that can expand when money is needed. The term "elastic currency" in the Federal Reserve Act does not just mean the ability to expand the money supply, but also to contract it. Some economic theories have been developed that support the idea of expanding or shrinking a money supply as economic conditions warrant. Elastic currency is defined by the Federal Reserve as:[38]

Currency that can, by the actions of the central monetary authority, expand or contract in amount warranted by economic conditions.

Monetary policy of the Federal Reserve System is based partially on the theory that it is best overall to expand or contract the money supply as economic conditions change.

Check Clearing System

Because some banks refused to clear checks from certain others during times of economic uncertainty, a check-clearing system was created in the Federal Reserve system. It is briefly described in The Federal Reserve System—Purposes and Functions as follows:[39]

By creating the Federal Reserve System, Congress intended to eliminate the severe financial crises that had periodically swept the nation, especially the sort of financial panic that occurred in 1907. During that episode, payments were disrupted throughout the country because many banks and clearinghouses refused to clear checks drawn on certain other banks, a practice that contributed to the failure of otherwise solvent banks. To address these problems, Congress gave the Federal Reserve System the authority to establish a nationwide check-clearing system. The System, then, was to provide not only an elastic currency—that is, a currency that would expand or shrink in amount as economic conditions warranted—but also an efficient and equitable check-collection system.

Lender of last resort

Emergencies

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, "the Federal Reserve has the authority and financial resources to act as 'lender of last resort' by extending credit to depository institutions or to other entities in unusual circumstances involving a national or regional emergency, where failure to obtain credit would have a severe adverse impact on the economy."[40] The Federal Reserve System's role as lender of last resort has been criticized because it shifts the risk and responsibility away from lenders and borrowers and places it on others in the form of inflation.[41]

Fluctuations

Through its discount and credit operations, Reserve Banks provide liquidity to banks to meet short-term needs stemming from seasonal fluctuations in deposits or unexpected withdrawals. Longer term liquidity may also be provided in exceptional circumstances. The rate the Fed charges banks for these loans is the discount rate (officially the primary credit rate).

By making these loans, the Fed serves as a buffer against unexpected day-to-day fluctuations in reserve demand and supply. This contributes to the effective functioning of the banking system, alleviates pressure in the reserves market and reduces the extent of unexpected movements in the interest rates.[42] For example, on September 16, 2008, the Federal Reserve Board authorized an $85 billion loan to stave off the bankruptcy of international insurance giant American International Group (AIG).[43][44]

Central bank

In its role as the central bank of the United States, the Fed serves as a banker's bank and as the government's bank. As the banker's bank, it helps to assure the safety and efficiency of the payments system. As the government's bank, or fiscal agent, the Fed processes a variety of financial transactions involving trillions of dollars. Just as an individual might keep an account at a bank, the U.S. Treasury keeps a checking account with the Federal Reserve, through which incoming federal tax deposits and outgoing government payments are handled. As part of this service relationship, the Fed sells and redeems U.S. government securities such as savings bonds and Treasury bills, notes and bonds. It also issues the nation's coin and paper currency. The U.S. Treasury, through its Bureau of the Mint and Bureau of Engraving and Printing, actually produces the nation's cash supply and, in effect, sells the paper currency to the Federal Reserve Banks at manufacturing cost, and the coins at face value. The Federal Reserve Banks then distribute it to other financial institutions in various ways.[45] During the Fiscal Year 2008, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing delivered 7.7 billion notes at an average cost of 6.4 cents per note.[46]

Federal funds

Federal funds are the reserve balances (also called federal reserve accounts) that private banks keep at their local Federal Reserve Bank.[47][48] These balances are the namesake reserves of the Federal Reserve System. The purpose of keeping funds at a Federal Reserve Bank is to have a mechanism for private banks to lend funds to one another. This market for funds plays an important role in the Federal Reserve System as it is what inspired the name of the system and it is what is used as the basis for monetary policy. Monetary policy works by influencing how much money the private banks charge each other for the lending of these funds.

Federal reserve accounts contain federal reserve credit, which can be converted into federal reserve notes. Private banks maintain their bank reserves in federal reserve accounts.

Balance between private banks and responsibility of governments

The system was designed out of a compromise between the competing philosophies of privatization and government regulation. In 2006 Donald L. Kohn, vice chairman of the Board of Governors, summarized the history of this compromise:[49]

Agrarian and progressive interests, led by William Jennings Bryan, favored a central bank under public, rather than banker, control. But the vast majority of the nation's bankers, concerned about government intervention in the banking business, opposed a central bank structure directed by political appointees.The legislation that Congress ultimately adopted in 1913 reflected a hard-fought battle to balance these two competing views and created the hybrid public-private, centralized-decentralized structure that we have today.

In the current system, private banks are for-profit businesses but government regulation places restrictions on what they can do. The Federal Reserve System is a part of government that regulates the private banks. The balance between privatization and government involvement is also seen in the structure of the system. Private banks elect members of the board of directors at their regional Federal Reserve Bank while the members of the Board of Governors are selected by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. The private banks give input to the government officials about their economic situation and these government officials use this input in Federal Reserve policy decisions. In the end, private banking businesses are able to run a profitable business while the U.S. government, through the Federal Reserve System, oversees and regulates the activities of the private banks.

Government regulation and supervision

Federal Banking Agency Audit Act enacted in 1978 as Public Law 95-320 and Section 31 USC 714 of U.S. Code establish that the Federal Reserve may be audited by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).[50] The GAO has authority to audit check-processing, currency storage and shipments, and some regulatory and bank examination functions, however there are restrictions to what the GAO may in fact audit. Audits of the Reserve Board and Federal Reserve banks may not include:

- transactions for or with a foreign central bank or government, or nonprivate international financing organization;

- deliberations, decisions, or actions on monetary policy matters;

- transactions made under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee; or

- a part of a discussion or communication among or between members of the Board of Governors and officers and employees of the Federal Reserve System related to items (1), (2), or (3).[51][52]

The financial crisis which began in 2007, corporate bailouts, and concerns over the Fed's secrecy have brought renewed concern regarding ability of the Fed to effectively manage the national monetary system.[53] A July 2009 Gallup Poll found only 30% Americans thought the Fed was doing a good or excellent job, a rating even lower than that for the Internal Revenue Service, which drew praise from 40%.[54] The Federal Reserve Transparency Act was introduced by congressman Ron Paul in order to obtain a more detailed audit of the Fed. The Fed has since hired Linda Robertson who headed the Washington lobbying office of Enron Corp. and was adviser to all three of the Clinton administration's Treasury secretaries.[55][56][57][58]

The Board of Governors in the Federal Reserve System has a number of supervisory and regulatory responsibilities in the U.S. banking system, but not complete responsibility. A general description of the types of regulation and supervision involved in the U.S. banking system is given by the Federal Reserve:[59]

The Board also plays a major role in the supervision and regulation of the U.S. banking system. It has supervisory responsibilities for state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, bank holding companies (companies that control banks), the foreign activities of member banks, the U.S. activities of foreign banks, and Edge Act and agreement corporations (limited-purpose institutions that engage in a foreign banking business). The Board and, under delegated authority, the Federal Reserve Banks, supervise approximately 900 state member banks and 5,000 bank holding companies. Other federal agencies also serve as the primary federal supervisors of commercial banks; the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency supervises national banks, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation supervises state banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System.Some regulations issued by the Board apply to the entire banking industry, whereas others apply only to member banks, that is, state banks that have chosen to join the Federal Reserve System and national banks, which by law must be members of the System. The Board also issues regulations to carry out major federal laws governing consumer credit protection, such as the Truth in Lending, Equal Credit Opportunity, and Home Mortgage Disclosure Acts. Many of these consumer protection regulations apply to various lenders outside the banking industry as well as to banks.

Members of the Board of Governors are in continual contact with other policy makers in government. They frequently testify before congressional committees on the economy, monetary policy, banking supervision and regulation, consumer credit protection, financial markets, and other matters.

The Board has regular contact with members of the President's Council of Economic Advisers and other key economic officials. The Chairman also meets from time to time with the President of the United States and has regular meetings with the Secretary of the Treasury. The Chairman has formal responsibilities in the international arena as well.

Preventing asset bubbles

The board of directors of each Federal Reserve Bank District also has regulatory and supervisory responsibilities. For example, a member bank (private bank) is not permitted to give out too many loans to people who cannot pay them back. This is because too many defaults on loans will lead to a bank run. If the board of directors has judged that a member bank is performing or behaving poorly, it will report this to the Board of Governors. This policy is described in United States Code:[60]

Each Federal reserve bank shall keep itself informed of the general character and amount of the loans and investments of its member banks with a view to ascertaining whether undue use is being made of bank credit for the speculative carrying of or trading in securities, real estate, or commodities, or for any other purpose inconsistent with the maintenance of sound credit conditions; and, in determining whether to grant or refuse advances, rediscounts, or other credit accommodations, the Federal reserve bank shall give consideration to such information. The chairman of the Federal reserve bank shall report to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System any such undue use of bank credit by any member bank, together with his recommendation. Whenever, in the judgment of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, any member bank is making such undue use of bank credit, the Board may, in its discretion, after reasonable notice and an opportunity for a hearing, suspend such bank from the use of the credit facilities of the Federal Reserve System and may terminate such suspension or may renew it from time to time.

The punishment for making false statements or reports that overvalue an asset is also stated in the U.S. Code:[61]

Whoever knowingly makes any false statement or report, or willfully overvalues any land, property or security, for the purpose of influencing in any way...shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 30 years, or both.

These aspects of the Federal Reserve System are the parts intended to prevent or minimize speculative asset bubbles, which ultimately lead to severe market corrections. The recent bubbles and corrections in energies, grains, equity and debt products and real estate cast doubt on the efficacy of these controls.

National payments system

[62] The Federal Reserve plays an important role in the U.S. payments system. The twelve Federal Reserve Banks provide banking services to depository institutions and to the federal government. For depository institutions, they maintain accounts and provide various payment services, including collecting checks, electronically transferring funds, and distributing and receiving currency and coin. For the federal government, the Reserve Banks act as fiscal agents, paying Treasury checks; processing electronic payments; and issuing, transferring, and redeeming U.S. government securities.

In passing the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, Congress reaffirmed its intention that the Federal Reserve should promote an efficient nationwide payments system. The act subjects all depository institutions, not just member commercial banks, to reserve requirements and grants them equal access to Reserve Bank payment services. It also encourages competition between the Reserve Banks and private-sector providers of payment services by requiring the Reserve Banks to charge fees for certain payments services listed in the act and to recover the costs of providing these services over the long run.

The Federal Reserve plays a vital role in both the nation's retail and wholesale payments systems, providing a variety of financial services to depository institutions. Retail payments are generally for relatively small-dollar amounts and often involve a depository institution's retail clients—individuals and smaller businesses. The Reserve Banks' retail services include distributing currency and coin, collecting checks, and electronically transferring funds through the automated clearinghouse system. By contrast, wholesale payments are generally for large-dollar amounts and often involve a depository institution's large corporate customers or counterparties, including other financial institutions. The Reserve Banks' wholesale services include electronically transferring funds through the Fedwire Funds Service and transferring securities issued by the U.S. government, its agencies, and certain other entities through the Fedwire Securities Service. Because of the large amounts of funds that move through the Reserve Banks every day, the System has policies and procedures to limit the risk to the Reserve Banks from a depository institution's failure to make or settle its payments.

The Federal Reserve Banks began a multi-year restructuring of their check operations in 2003 as part of a long-term strategy to respond to the declining use of checks by consumers and businesses and the greater use of electronics in check processing. The Reserve Banks will have reduced the number of full-service check processing locations from 45 in 2003 to 4 by early 2011.[63]

Structure

The Federal Reserve System has both private and public components, and can make decisions without the permission of Congress or the President of the U.S.[64] The System does not require public funding, and derives its authority and public purpose from the Federal Reserve Act passed by Congress in 1913. The two main aspects of the Federal Reserve System are the Federal Open Market Committee and regional Federal Reserve Banks located throughout the country.

Board of Governors

The seven-member Board of Governors is a federal agency that is the main governing body of the Federal Reserve System. It is charged with overseeing the 12 District Reserve Banks and with helping implement national monetary policy. It also supervises and regulates the U.S. banking system in general.[65] Governors are appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate for staggered 14-year terms.[42] The terms of the seven members of the Board span multiple presidential and congressional terms. The Board is required to make an annual report of operations to the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Board of Governors are appointed by the President from among the sitting Governors. They both serve a four year term and they can be renominated as many times as possible until their term on the Board of Governors expires, but—regardless of whether either is reconfirmed for their chairmanship or vice chairmanship—he or she is free to complete their term on the Board of Governors.[66]

List of members of the Board of Governors

The current members of the Board of Governors are as follows:[67]

| Commissioner | Entered office[68] | Term expires |

|---|---|---|

| Ben Bernanke (Chairman) |

February 1, 2006 | January 31, 2020 January 31, 2014 (as Chair) |

| Donald Kohn (Vice Chairman) |

August 5, 2006 June 23, 2006 (as VC) |

January 31, 2016 June 22, 2010 (as VC) |

| Kevin Warsh | February 24, 2006 | January 31, 2018 |

| Elizabeth Duke | August 5, 2008 | January 31, 2012 |

| Daniel Tarullo | January 28, 2009 | January 31, 2022 |

| Vacant | —— | January 31, 2014 |

| Vacant | —— | January 31, 2024 |

On March 2, 2010, Kohn announced his retirement in June 2010[69] and, on April 29, Barack Obama nominated three people to fill the vacancies: the economist Janet L. Yellen, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; and Peter A. Diamond, an M.I.T. economist who is an authority on Social Security, pensions, and taxation; and Sarah Bloom Raskin, an attorney who is Maryland's Commissioner of Financial Regulation.[70] Yellin was also nominated to serve as vice chairman. Commentators expect the nominees to be confirmed.[71] If the three are confirmed, Yellin's term will expire in 2024 (only months short of a full term), Diamond's term in 2014, and Bloom's in 2016, and the board would be at full strength for the first time in nearly four years.[71]

Federal Open Market Committee

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) consists of 12 members, seven from the Board of Governors and five representatives from the regional Federal Reserve Banks. The FOMC oversees open market operations, the principal tool of national monetary policy. These operations affect the amount of Federal Reserve balances available to depository institutions, thereby influencing overall monetary and credit conditions. The FOMC also directs operations undertaken by the Federal Reserve in foreign exchange markets. The representative from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, is a permanent member, while the rest of the banks rotate at two- and three-year intervals. All the presidents participate in FOMC discussions, contributing to the committee's assessment of the economy and of policy options, but only the five presidents who are committee members vote on policy decisions. The FOMC determines its own internal organization and by tradition elects the Chairman of the Board of Governors as its chairman and the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York as its vice chairman. Formal meetings typically are held eight times each year in Washington, D.C. Nonvoting Reserve Bank presidents also participate in Committee deliberations and discussion. The FOMC generally meets eight times a year in Telephone consultations and other meetings are held when needed.[72] It is informal policy, within the FOMC, for the Board of Governors and the New York Federal Reserve Bank president to vote with the Chairman of the FOMC. Additionally, anyone who is not an expert on monetary policy traditionally votes with the chairman as well. On all votes, no more than two FOMC members can dissent.[73]

Federal Reserve Banks

There are 12 Federal Reserve Banks which are located in the following cities: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco. Each reserve Bank is responsible for member banks located in its district. The size of each district was set based upon the population distribution at the time the Federal Reserve Act was passed. Each regional Bank has a president, who is the chief executive officer of the Bank. The regional Reserve Bank presidents are nominated by the Bank's board of directors, but their nomination is contingent upon approval by the Board of Governors. Presidents serve five year terms and may be reappointed.[74]

Each regional Bank's board consists of nine members. Members are broken down into three classes: class A, class B, and class C. There are three board members in each class. Class A members are chosen by the regional Bank's shareholders, and are intended to represent member banks' interests. Member banks are divided into large, medium, and small. Each size bank elects one of the three class A board members. Class B board members are also nominated by the region's member banks, but class B board members are supposed to represent the interests of the public. Lastly, class C board members are nominated by the Board of Governors, and are also intended to represent the interests of the public.[75]

A member bank is a private bank that owns stock in its regional Federal Reserve Bank. All nationally chartered banks hold stock in one of the Federal Reserve Banks. State chartered banks may choose to be members (and hold stock in their regional Federal Reserve bank), upon meeting certain standards. The amount of stock a member bank must own is equal to 3% of its combined capital and surplus.[76] Holding stock in a Federal Reserve bank is not, however, like owning publicly traded stock. The stock cannot be sold or traded.[77] From the profit of the regional banks, member banks receive a dividend equal to 6% of the stock it owns in the regional Reserve Bank.[64] The remainder of a regional Federal Reserve Bank's profit is given to the United States Treasury Department. In 2009, the Federal Reserve Banks distributed $1.4 billion in dividends to member banks and returned $47 billion to the U.S. Treasury.[78]

Legal status of regional Federal Reserve Banks

The Federal Reserve Banks have an intermediate legal status, with some features of private corporations and some features of public federal agencies. The United States has an interest in the Federal Reserve Banks as tax-exempt federally-created instrumentalities whose profits belong to the federal government, but this interest is not proprietary.[79] Each member bank (commercial banks in the Federal Reserve district) owns a nonnegotiable share of stock in its regional Federal Reserve Bank. However, holding Federal Reserve Bank stock is unlike owning stock in a publicly traded company. The charter of each Federal Reserve Bank is established by law and cannot be altered by the member banks. Federal Reserve Bank stock cannot be sold or traded, and member banks do not control the Federal Reserve Bank as a result of owning this stock. They do, however, elect six of the nine members of the Federal Reserve Banks' boards of directors.[42] In Lewis v. United States,[80] the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit stated that: "The Reserve Banks are not federal instrumentalities for purposes of the FTCA [the Federal Tort Claims Act], but are independent, privately owned and locally controlled corporations." The opinion went on to say, however, that: "The Reserve Banks have properly been held to be federal instrumentalities for some purposes." Another relevant decision is Scott v. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,[79] in which the distinction is made between Federal Reserve Banks, which are federally-created instrumentalities, and the Board of Governors, which is a federal agency.

Monetary policy

The term "monetary policy" refers to the actions undertaken by a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve, to influence the availability and cost of money and credit to help promote national economic goals. What happens to money and credit affects interest rates (the cost of credit) and the performance of the U.S. economy. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave the Federal Reserve responsibility for setting monetary policy.[81][82]

Interbank lending is the basis of policy

The Federal Reserve implements monetary policy by influencing the interbank lending of excess reserves. The rate that banks charge each other for these loans is determined by the markets but the Federal Reserve influences this rate through the three tools of monetary policy described in the "Tools" section below. This is a short-term interest rate the FOMC focuses on directly. This rate ultimately affects the longer-term interest rates throughout the economy. A summary of the basis and implementation of monetary policy is stated by the Federal Reserve:

The Federal Reserve implements U.S. monetary policy by affecting conditions in the market for balances that depository institutions hold at the Federal Reserve Banks...By conducting open market operations, imposing reserve requirements, permitting depository institutions to hold contractual clearing balances, and extending credit through its discount window facility, the Federal Reserve exercises considerable control over the demand for and supply of Federal Reserve balances and the federal funds rate. Through its control of the federal funds rate, the Federal Reserve is able to foster financial and monetary conditions consistent with its monetary policy objectives.—[83]

This influences the economy through its effect on the quantity of reserves that banks use to make loans. Policy actions that add reserves to the banking system encourage lending at lower interest rates thus stimulating growth in money, credit, and the economy. Policy actions that absorb reserves work in the opposite direction. The Fed's task is to supply enough reserves to support an adequate amount of money and credit, avoiding the excesses that result in inflation and the shortages that stifle economic growth.[84]

Goals

The goals of monetary policy include:[6][82]

- maximum employment

- stable prices

- moderate long-term interest rates

- promotion of sustainable economic growth

Tools

There are three main tools of monetary policy that the Federal Reserve uses to influence the amount of reserves in private banks:[81]

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| open market operations | purchases and sales of U.S. Treasury and federal agency securities—the Federal Reserve's principal tool for implementing monetary policy. The Federal Reserve's objective for open market operations has varied over the years. During the 1980s, the focus gradually shifted toward attaining a specified level of the federal funds rate (the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed), a process that was largely complete by the end of the decade.[85] |

| discount rate | the interest rate charged to commercial banks and other depository institutions on loans they receive from their regional Federal Reserve Bank's lending facility—the discount window.[86] |

| reserve requirements | the amount of funds that a depository institution must hold in reserve against specified deposit liabilities.[87] |

Open market operations

Open market operations put money in and take money out of the banking system. This is done through the sale and purchase of U.S. government treasury securities. When the U.S. government sells securities, it gets money from the banks and the banks get a piece of paper (I.O.U.) that says the U.S. government owes the bank money. This drains money from the banks. When the U.S. government buys securities, it gives money to the banks and the banks give the I.O.U. back to the U.S. government. This puts money back into the banks. The Federal Reserve education website describes open market operations as follows:[82]

Open market operations involve the buying and selling of U.S. government securities (federal agency and mortgage-backed). The term 'open market' means that the Fed doesn't decide on its own which securities dealers it will do business with on a particular day. Rather, the choice emerges from an 'open market' in which the various securities dealers that the Fed does business with—the primary dealers—compete on the basis of price. Open market operations are flexible and thus, the most frequently used tool of monetary policy.Open market operations are the primary tool used to regulate the supply of bank reserves. This tool consists of Federal Reserve purchases and sales of financial instruments, usually securities issued by the U.S. Treasury, Federal agencies and government-sponsored enterprises. Open market operations are carried out by the Domestic Trading Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York under direction from the FOMC. The transactions are undertaken with primary dealers.

The Fed's goal in trading the securities is to affect the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks borrow reserves from each other. When the Fed wants to increase reserves, it buys securities and pays for them by making a deposit to the account maintained at the Fed by the primary dealer's bank. When the Fed wants to reduce reserves, it sells securities and collects from those accounts. Most days, the Fed does not want to increase or decrease reserves permanently so it usually engages in transactions reversed within a day or two. That means that a reserve injection today could be withdrawn tomorrow morning, only to be renewed at some level several hours later. These short-term transactions are called repurchase agreements (repos) – the dealer sells the Fed a security and agrees to buy it back at a later date.

A simpler description is described in The Federal Reserve in Plain English:[88]

How do open market operations actually work? Currently, the FOMC establishes a target for the federal funds rate (the rate banks charge each other for overnight loans). Open market purchases of government securities increase the amount of reserve funds that banks have available to lend, which puts downward pressure on the federal funds rate. Sales of government securities do just the opposite—they shrink the reserve funds available to lend and tend to raise the funds rate.By targeting the federal funds rate, the FOMC seeks to provide the monetary stimulus required to foster a healthy economy. After each FOMC meeting, the funds rate target is announced to the public.

Repurchase agreements

To smooth temporary or cyclical changes in the monetary supply, the desk engages in repurchase agreements (repos) with its primary dealers. Repos are essentially secured, short-term lending by the Fed. On the day of the transaction, the Fed deposits money in a primary dealer's reserve account, and receives the promised securities as collateral. When the transaction matures, the process unwinds: the Fed returns the collateral and charges the primary dealer's reserve account for the principal and accrued interest. The term of the repo (the time between settlement and maturity) can vary from 1 day (called an overnight repo) to 65 days.[89]

Federal funds rate and discount rate

The Federal Reserve System implements monetary policy largely by targeting the federal funds rate. This is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed. This rate is actually determined by the market and is not explicitly mandated by the Fed. The Fed therefore tries to align the effective federal funds rate with the targeted rate by adding or subtracting from the money supply through open market operations. The late economist Milton Friedman consistently criticized this reverse method of controlling inflation by seeking an ideal interest rate and enforcing it through affecting the money supply since nowhere in the widely accepted money supply equation are interest rates found.[90]

The Federal Reserve System also directly sets the "discount rate", which is the interest rate for "discount window lending", overnight loans that member banks borrow directly from the Fed. This rate is generally set at a rate close to 100 basis points above the target federal funds rate. The idea is to encourage banks to seek alternative funding before using the "discount rate" option.[91] The equivalent operation by the European Central Bank is referred to as the "marginal lending facility".[92]

Both of these rates influence the prime rate, which is usually about 3 percent higher than the federal funds rate.

Lower interest rates stimulate economic activity by lowering the cost of borrowing, making it easier for consumers and businesses to buy and build, but at the cost of promoting the expansion of the money supply and thus greater inflation. Higher interest rates may slow the economy by increasing the cost of borrowing. (See monetary policy for a fuller explanation.)

The Federal Reserve System usually adjusts the federal funds rate by 0.25% or 0.50% at a time.

The Federal Reserve System might also attempt to use open market operations to change long-term interest rates, but its "buying power" on the market is significantly smaller than that of private institutions. The Fed can also attempt to "jawbone" the markets into moving towards the Fed's desired rates, but this is not always effective.

Reserve requirements

Another instrument of monetary policy adjustment employed by the Federal Reserve System is the fractional reserve requirement, also known as the required reserve ratio.[93] The required reserve ratio sets the balance that the Federal Reserve System requires a depository institution to hold in the Federal Reserve Banks,[83] which depository institutions trade in the federal funds market discussed above.[94] The required reserve ratio is set by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.[95] The reserve requirements have changed over time and some of the history of these changes is published by the Federal Reserve.[96]

| Type of liability | Requirement | |

| Percentage of liabilities | Effective date | |

| Net transaction accounts | ||

| $0 to $10.3 million | 0 | 01/01/09 |

| More than $10.3 million to $44.4 million | 3 | 01/01/09 |

| More than $44.4 million | 10 | 01/01/09 |

| Nonpersonal time deposits | 0 | 12/27/90 |

| Eurocurrency liabilities | 0 | 12/27/90 |

As a response to the financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve now makes interest payments on depository institutions' required and excess reserve balances. The payment of interest on excess reserves gives the central bank greater opportunity to address credit market conditions while maintaining the federal funds rate close to the target rate set by the FOMC.[97]

New facilities

In order to address problems related to the subprime mortgage crisis and United States housing bubble, several new tools have been created. The first new tool, called the Term Auction Facility, was added on December 12, 2007. It was first announced as a temporary tool[98] but there have been suggestions that this new tool may remain in place for a prolonged period of time.[99] Creation of the second new tool, called the Term Securities Lending Facility, was announced on March 11, 2008.[100] The main difference between these two facilities is that the Term Auction Facility is used to inject cash into the banking system whereas the Term Securities Lending Facility is used to inject treasury securities into the banking system.[101] Creation of the third tool, called the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), was announced on March 16, 2008.[102] The PDCF was a fundamental change in Federal Reserve policy because now the Fed is able to lend directly to primary dealers, which was previously against Fed policy.[103] The differences between these 3 new facilities is described by the Federal Reserve:[104]

The Term Auction Facility program offers term funding to depository institutions via a bi-weekly auction, for fixed amounts of credit. The Term Securities Lending Facility will be an auction for a fixed amount of lending of Treasury general collateral in exchange for OMO-eligible and AAA/Aaa rated private-label residential mortgage-backed securities. The Primary Dealer Credit Facility now allows eligible primary dealers to borrow at the existing Discount Rate for up to 120 days.

Some of the measures taken by the Federal Reserve to address this mortgage crisis haven't been used since The Great Depression.[105] The Federal Reserve gives a brief summary of what these new facilities are all about:[106]

As the economy has slowed in the last nine months and credit markets have become unstable, the Federal Reserve has taken a number of steps to help address the situation. These steps have included the use of traditional monetary policy tools at the macroeconomic level as well as measures at the level of specific markets to provide additional liquidity.The Federal Reserve's response has continued to evolve since pressure on credit markets began to surface last summer, but all these measures derive from the Fed's traditional open market operations and discount window tools by extending the term of transactions, the type of collateral, or eligible borrowers.

Term auction facility

The Term Auction Facility is a program in which the Federal Reserve auctions term funds to depository institutions.[98] The creation of this facility was announced by the Federal Reserve on December 12, 2007 and was done in conjunction with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank to address elevated pressures in short-term funding markets.[107] The reason it was created is because banks were not lending funds to one another and banks in need of funds were refusing to go to the discount window. Banks were not lending money to each other because there was a fear that the loans would not be paid back. Banks refused to go to the discount window because it is usually associated with the stigma of bank failure.[108][109][110][111] Under the Term Auction Facility, the identity of the banks in need of funds is protected in order to avoid the stigma of bank failure.[112] Foreign exchange swap lines with the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank were opened so the banks in Europe could have access to U.S. dollars.[112] Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke briefly described this facility to the U.S. House of Representatives on January 17, 2008:

the Federal Reserve recently unveiled a term auction facility, or TAF, through which prespecified amounts of discount window credit can be auctioned to eligible borrowers. The goal of the TAF is to reduce the incentive for banks to hoard cash and increase their willingness to provide credit to households and firms...TAF auctions will continue as long as necessary to address elevated pressures in short-term funding markets, and we will continue to work closely and cooperatively with other central banks to address market strains that could hamper the achievement of our broader economic objectives.[113]

It is also described in the Term Auction Facility FAQ[98]

The TAF is a credit facility that allows a depository institution to place a bid for an advance from its local Federal Reserve Bank at an interest rate that is determined as the result of an auction. By allowing the Federal Reserve to inject term funds through a broader range of counterparties and against a broader range of collateral than open market operations, this facility could help ensure that liquidity provisions can be disseminated efficiently even when the unsecured interbank markets are under stress.In short, the TAF will auction term funds of approximately one-month maturity. All depository institutions that are judged to be in sound financial condition by their local Reserve Bank and that are eligible to borrow at the discount window are also eligible to participate in TAF auctions. All TAF credit must be fully collateralized. Depositories may pledge the broad range of collateral that is accepted for other Federal Reserve lending programs to secure TAF credit. The same collateral values and margins applicable for other Federal Reserve lending programs will also apply for the TAF.

Term securities lending facility

The Term Securities Lending Facility is a 28-day facility that will offer Treasury general collateral to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's primary dealers in exchange for other program-eligible collateral. It is intended to promote liquidity in the financing markets for Treasury and other collateral and thus to foster the functioning of financial markets more generally.[114] Like the Term Auction Facility, the TSLF was done in conjunction with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank. The resource allows dealers to switch debt that is less liquid for U.S. government securities that are easily tradable. It is anticipated by Federal Reserve officials that the primary dealers, which include Goldman Sachs Group. Inc., J.P. Morgan Chase, and Morgan Stanley, will lend the Treasuries on to other firms in return for cash. That will help the dealers finance their balance sheets. The currency swap lines with the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank were increased.

Primary dealer credit facility

The Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) is an overnight loan facility that will provide funding to primary dealers in exchange for a specified range of eligible collateral and is intended to foster the functioning of financial markets more generally.[104] This new facility marks a fundamental change in Federal Reserve policy because now primary dealers can borrow directly from the Fed when this previously was not permitted.

Interest on reserves

As of October 2008[update], the Federal Reserve banks will pay interest on reserve balances (required & excess) held by depository institutions. The rate is set at the lowest federal funds rate during the reserve maintenance period of an institution, less 75bp.[115] As of October 23, 2008, the Fed has lowered the spread to a mere 35 bp.[116]

Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility

The Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (ABCPMMMFLF) was also called the AMLF. The Facility began operations on September 22, 2008, and was closed on February 1, 2010.[117]

All U.S. depository institutions, bank holding companies (parent companies or U.S. broker-dealer affiliates), or U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks were eligible to borrow under this facility pursuant to the discretion of the FRBB.

Collateral eligible for pledge under the Facility was required to meet the following criteria:

- was purchased by Borrower on or after September 19, 2008 from a registered investment company that held itself out as a money market mutual fund;

- was purchased by Borrower at the Fund's acquisition cost as adjusted for amortization of premium or accretion of discount on the ABCP through the date of its purchase by Borrower;

- was rated at the time pledged to FRBB, not lower than A1, F1, or P1 by at least two major rating agencies or, if rated by only one major rating agency, the ABCP must have been rated within the top rating category by that agency;

- was issued by an entity organized under the laws of the United States or a political subdivision thereof under a program that was in existence on September 18, 2008; and

- had a stated maturity that did not exceed 120 days if the Borrower was a bank or 270 days for non-bank Borrowers.

Commercial Paper Funding Facility

The Commercial Paper Funding Facility is also called the CPFF. On October 7, 2008 the Federal Reserve further expanded the collateral it will loan against, to include commercial paper. The action made the Fed a crucial source of credit for non-financial businesses in addition to commercial banks and investment firms. Fed officials said they'll buy as much of the debt as necessary to get the market functioning again. They refused to say how much that might be, but they noted that around $1.3 trillion worth of commercial paper would qualify. There was $1.61 trillion in outstanding commercial paper, seasonally adjusted, on the market as of October 1, 2008, according to the most recent data from the Fed. That was down from $1.70 trillion in the previous week. Since the summer of 2007, the market has shrunk from more than $2.2 trillion.[118]

Money Market Investor Funding Facility

The Money Market Investor Funding Facility is also called the MMIFF. The Federal Reserve introduced a facility on October 21, 2008, whereby money market mutual funds can set up a structured investment vehicle of short-term assets underwritten by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.[119] The program will run until April 30, 2009, unless extended by the FRB.

Quantitative policy

Another policy that can be used is a little used tool of the Federal Reserve (U.S. central bank) that is known as the quantitative policy. With that the Federal Reserve actually buys back corporate bonds and mortgage backed securities held by banks or other financial institutions. This in effect puts money back into the financial institutions and allows them to make loans and conduct normal business. The Federal Reserve Board used this policy in the early nineties when the U.S. economy experienced the Savings and Loan crisis.

Quantitative easing

Quantitative easing is another way to influence monetary policy, only recently begun to be used in the United States. Other countries, such as Japan, have provided a template for some Fed actions. Essentially, quantitative easing provides a method for the central bank to provide funds at lower than zero interest rates, in order to increase the monetary supply and combat deflationary forces. This is accomplished by the Fed purchasing U.S. government debt with newly printed U.S. currency. In essence, the Fed is monetizing the debt. In the current (late 2007 to today) macro-economic environment, the slowing velocity of money has induced U.S. central bankers to pursue a variety of new, and to some radical, policies to produce economic stimulus.

Uncertainties

A few of the uncertainties involved in monetary policy decision making are described by the federal reserve:[120]

- While these policy choices seem reasonably straightforward, monetary policy makers routinely face certain notable uncertainties. First, the actual position of the economy and growth in aggregate demand at any time are only partially known, as key information on spending, production, and prices becomes available only with a lag. Therefore, policy makers must rely on estimates of these economic variables when assessing the appropriate course of policy, aware that they could act on the basis of misleading information. Second, exactly how a given adjustment in the federal funds rate will affect growth in aggregate demand—in terms of both the overall magnitude and the timing of its impact—is never certain. Economic models can provide rules of thumb for how the economy will respond, but these rules of thumb are subject to statistical error. Third, the growth in aggregate supply, often called the growth in potential output, cannot be measured with certainty.

- In practice, as previously noted, monetary policy makers do not have up-to-the-minute information on the state of the economy and prices. Useful information is limited not only by lags in the construction and availability of key data but also by later revisions, which can alter the picture considerably. Therefore, although monetary policy makers will eventually be able to offset the effects that adverse demand shocks have on the economy, it will be some time before the shock is fully recognized and—given the lag between a policy action and the effect of the action on aggregate demand—an even longer time before it is countered. Add to this the uncertainty about how the economy will respond to an easing or tightening of policy of a given magnitude, and it is not hard to see how the economy and prices can depart from a desired path for a period of time.

- The statutory goals of maximum employment and stable prices are easier to achieve if the public understands those goals and believes that the Federal Reserve will take effective measures to achieve them.

- Although the goals of monetary policy are clearly spelled out in law, the means to achieve those goals are not. Changes in the FOMC's target federal funds rate take some time to affect the economy and prices, and it is often far from obvious whether a selected level of the federal funds rate will achieve those goals.

Measurement of economic variables

A lot of data is recorded and published by the Federal Reserve. A few websites where data is published are at the Board of Governors Economic Data and Research page,[121] the Board of Governors statistical releases and historical data page,[122] and at the St. Louis Fed's FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) page.[123] The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) examines many economic indicators prior to determining monetary policy.[124]

Net worth of households and nonprofit organizations

The net worth of households and nonprofit organizations in the United States is published by the Federal Reserve in a report titled, Flow of Funds.[125] At the end of fiscal year 2008, this value was $51.5 trillion.

Money supply

The most common measures are named M0 (narrowest), M1, M2, and M3. In the United States they are defined by the Federal Reserve as follows:

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| M0 | The total of all physical currency, plus accounts at the central bank that can be exchanged for physical currency. |

| M1 | M0 + those portions of M0 held as reserves or vault cash + the amount in demand accounts ("checking" or "current" accounts). |

| M2 | M1 + most savings accounts, money market accounts, and small denomination time deposits (certificates of deposit of under $100,000). |

| M3 | M2 + all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements. |

The Federal Reserve ceased publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, explaining that it cost a lot to collect the data but did not provide significantly useful information.[126] The other three money supply measures continue to be provided in detail.

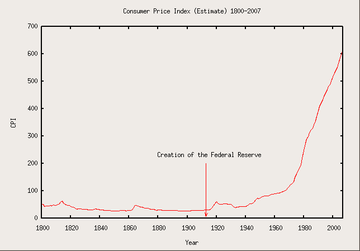

Consumer price index

The consumer price index is used as one measure of the value of money. It is defined as:

A measure of the average price level of a fixed basket of goods and services purchased by consumers as determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Monthly changes in the CPI represent the rate of inflation. Core CPI excludes volatile components, i.e., food and energy prices.

The data consists of the U.S. city average of consumer prices and can be found at The U.S. Department of Labor—Bureau of Labor Statistics[127]

The CPI taken alone is not a complete measure of the value of money. For example, the monetary value of stocks, real estate, and other goods and services categorized as investment vehicles are not reflected in the CPI. It is difficult to obtain a full picture of value across the full range of the cost of living, so the CPI is typically used as a substitute. The CPI therefore has powerful political ramifications, and Administrations of both parties have been tempted to change the basis for its calculation, progressively underestimating the true rate of decline in purchasing power.[128] A controversial method used in calculating CPI is "hedonic adjustments". The basic concept applies a discount for the assumed increased utility of products (i.e. faster CPU processing speeds of computers). However, consumers rarely make decisions based upon the price per computer processing cycle. An argument can be made that such hedonic adjustments significantly contribute to understating true inflation experienced by consumers buying everyday goods and services.[129]

One of the Fed's main roles is to maintain price stability. This means that the change in the consumer price index over time should be as small as possible. The ability to maintain a low inflation rate is a long-term measure of the Fed's success.[130] Although the Fed usually tries to keep the year-on-year change in CPI between 2 and 3 percent,[131] there has been debate among policy makers as to whether or not the Federal Reserve should have a specific inflation targeting policy.[132][133][134]

Inflation and the economy

There are two types of inflation that are closely tied to each other. Monetary inflation is an increase in the money supply. Price inflation is a sustained increase in the general level of prices, which is equivalent to a decline in the value or purchasing power of money. If the supply of money and credit increases too rapidly over many months (monetary inflation), the result will usually be price inflation. Price inflation does not always increase in direct proportion to monetary inflation; it is also affected by the velocity of money and other factors. With price inflation, a dollar buys less and less over time.[82]

The effects of monetary and price inflation include:[82]

- Price inflation makes workers worse off if their incomes don't rise as rapidly as prices.

- Pensioners living on a fixed income are worse off if their savings do not increase more rapidly than prices.

- Lenders lose because they will be repaid with dollars that aren't worth as much.

- Savers lose because the dollar they save today will not buy as much when they are ready to spend it.

- Businesses and people will find it harder to plan and therefore may decrease investment in future projects.

- Owners of financial assets suffer.

- Interest rate-sensitive industries, like mortgage companies, suffer as monetary inflation drives up long-term interest rates and Federal Reserve tightening raises short-term rates.

Unemployment rate

The unemployment rate statistics are collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since one of the stated goals of monetary policy is maximum employment, the unemployment rate is a sign of the success of the Federal Reserve System.

Like the CPI, the unemployment rate is used as a barometer of the nation's economic health, and thus as a measure of the success of an administration's economic policies. Since 1980, both parties have made progressive changes in the basis for calculating unemployment, so that the numbers now quoted cannot be compared directly to the corresponding rates from earlier administrations, or to the rest of the world.[135]

Budget

The Federal Reserve is self-funded. The vast majority (90%+) of Fed revenues come from open market operations, specifically the interest on the portfolio of Treasury securities as well as "capital gains/losses" that may arise from the buying/selling of the securities and their derivatives as part of Open Market Operations. The balance of revenues come from sales of financial services (check and electronic payment processing) and discount window loans.[136] The Board of Governors (Federal Reserve Board) creates a budget report once per year for Congress. There are two reports with budget information. The one that lists the complete balance statements with income and expenses as well as the net profit or loss is the large report simply titled, "Annual Report". It also includes data about employment throughout the system. The other report, which explains in more detail the expenses of the different aspects of the whole system, is called "Annual Report: Budget Review". These are comprehensive reports with many details and can be found at the Board of Governors' website under the section "Reports to Congress"[137]

Net worth

Balance sheet

One of the keys to understanding the Federal Reserve is the Federal Reserve balance sheet (or balance statement). In accordance with Section 11 of the Federal Reserve Act, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System publishes once each week the "Consolidated Statement of Condition of All Federal Reserve Banks" showing the condition of each Federal Reserve bank and a consolidated statement for all Federal Reserve banks. The Board of Governors requires that excess earnings of the Reserve Banks be transferred to the Treasury as interest on Federal Reserve notes.[138][139]

Below is the balance sheet as of April 22, 2009 (in millions of dollars):

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analyzing the Federal Reserve's balance sheet reveals a number of facts:

- The Fed has over $11 billion in gold, which is a holdover from the days the government used to back U.S. Notes and Federal Reserve Notes with gold.. The value reported here is based on a statutory valuation of $42 2/9 per fine troy ounce. As of March 2009, the market value of that gold is around $247.8 billion.

- The Fed holds more than $1.8 billion in coinage, not as a liability but as an asset. The Treasury Department is actually in charge of creating coins and U.S. Notes. The Fed then buys coinage from the Treasury by increasing the liability assigned to the Treasury's account.

- The Fed holds at least $534 billion of the national debt. The "securities held outright" value used to directly represent the Fed's share of the national debt, but after the creation of new facilities in the winter of 2007-2008, this number has been reduced and the difference is shown with values from some of the new facilities.

- The Fed has no assets from overnight repurchase agreements. Repurchase agreements are the primary asset of choice for the Fed in dealing in the open market. Repo assets are bought by creating 'depository institution' liabilities and directed to the bank the primary dealer uses when they sell into the open market.

- The more than $1 trillion in Federal Reserve Note liabilities represents nearly the total value of all dollar bills in existence; over $176 billion is held by the Fed (not in circulation); and the "net" figure of $863 billion represents the total face value of Federal Reserve Notes in circulation.

- The $916 billion in deposit liabilities of depository institutions shows that dollar bills are not the only source of government money. Banks can swap deposit liabilities of the Fed for Federal Reserve Notes back and forth as needed to match demand from customers, and the Fed can have the Bureau of Engraving and Printing create the paper bills as needed to match demand from banks for paper money. The amount of money printed has no relation to the growth of the monetary base (M0).

- The $93.5 billion in Treasury liabilities shows that the Treasury Department does not use private banks but rather uses the Fed directly (the lone exception to this rule is Treasury Tax and Loan because government worries that pulling too much money out of the private banking system during tax time could be disruptive).

- The $1.6 billion foreign liability represents the amount of foreign central bank deposits with the Federal Reserve.

- The $9.7 billion in 'other liabilities and accrued dividends' represents partly the amount of money owed so far in the year to member banks for the 6% dividend on the 3% of their net capital they are required to contribute in exchange for nonvoting stock their regional Reserve Bank in order to become a member. Member banks are also subscribed for an additional 3% of their net capital, which can be called at the Federal Reserve's discretion. All nationally chartered banks must be members of a Federal Reserve Bank, and state-chartered banks have the choice to become members or not.